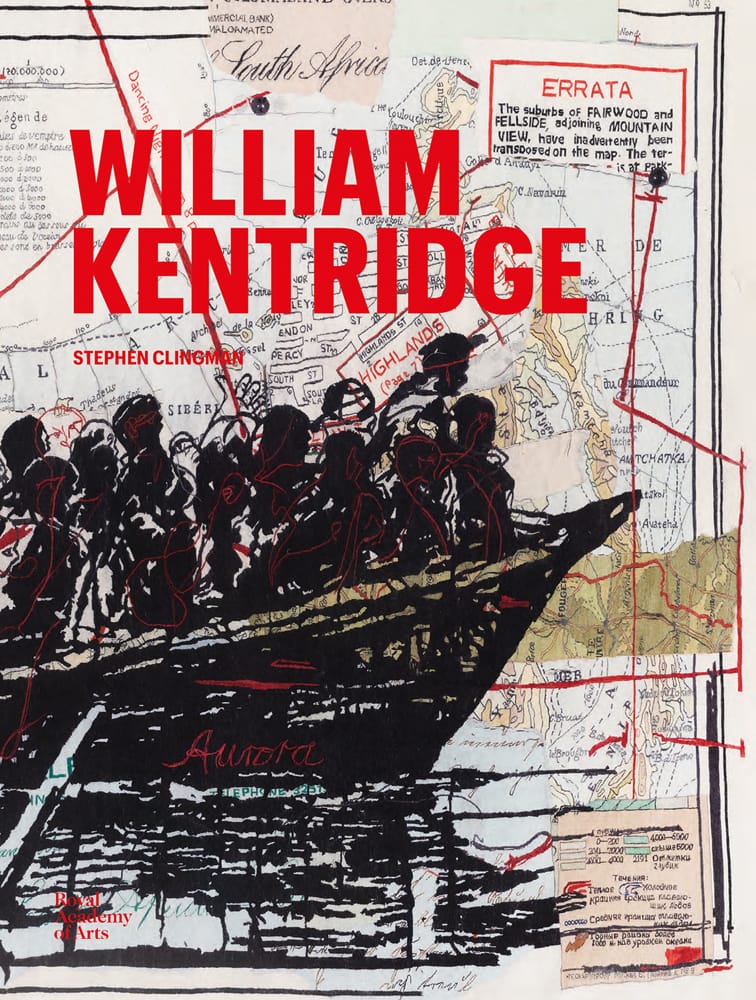

A Review on Willliam Kentridge’s Royal Academy Catalogue authored by Stephen Clingham

So, who is William Kentridge? In the world of sophisticated art fanatics, there’s no doubt that this question isn’t considered as sacrilege. The irony of figures whose genius turns them into giants is that they turn somewhat invisible to the everyday passer-by. The celebrated name bounces across the room like endless echoes until it becomes just that. A name. The person behind is somewhat lost. At least that was the case for me. He was a name that I felt programmed to revere but struggled to connect with. It was not until reading Stephen Clingman’s exceptional rendition of Kentridge’s life that I truly understood why the terms ‘ground-breaking,’ ‘genius,’ and ‘seminal’ are used to describe the eponymous artist.

As the writer Horace Howard Furness once said:

“I am convinced that were I told that my closest friend was lying at the point of death, and that his life could be saved by permitting him to divulge his theory of Hamlet, I would instantly say, ‘Let him die! Let him die! Let him die!”

I think it’s fit to say ‘Hamlet’ can be substituted by William Kentridge. So, what is it about Stephen Clingman’s book that deserves the centre stage among the wellspring of others. Well, I’ll let you in as to why this latest book on Kentridge is a must-have for any art or Kentridge-lover.

Having cultivated his talents from drawing, animation, sculpture, collage, puppetry, opera (the list goes on) for over forty years, it is undeniable that Clingman ventured on a challenging feat by compressing the personage of William Kentridge between pages. Yet, he not only achieves this with a personal and intellectual depth, but he provides a cerebral roadmap for the reader, that almost makes you believe you’re walking through Kentridge’s mind. Whether it is his accomplishments as an English Professor or the fact that he is also a South African (perhaps the two combined), it is no doubt that the job was assigned brilliantly. Clingman eloquently cements the often-overlooked bridge between the fine arts and the literary world. The parallels drawn between the two are stark and memorable, describing Kentridge as one who “discovers the new through a play of differences, oppositions and unexpected analogies,” and that he builds his work on metonymy: “contiguity, adjacency and association: one form edges or transforms into another.” He paints the sort of cognitive optical illusions that Kentridge plays with but makes the abstract concrete by describing how Kentridge’s objects “will become another iteration of itself …as lines are blurred, erased or reconstituted.”

The fluidity and with it the multitude of meaning of Kentridge’s art is dissected with precision but also with a want for a receptive and captivated audience.

Beginning with reflective writings on William Kentridge as just an artist and a person, just glazing the eye at the headings lures you in: Liberating Vision; The Less Good Doctor, Transformation etc. Within each of these we get a taste for the origin of Kentridge’s unconventionality, the importance of play in his work and how his political history and involvement feeds into the nature of his creations.

Clingman gives a moving reflection on political paradigms and how Kentridge subtly exposes and steps out of them at the same time:

“But apartheid was more than a political regime but a “regime of seeing, a way of seeing the world in which everything was governed by its supposed logic, moralities, rationanalities, divisions, structures and boundaries.”

Much like the Kentridge’s Triumphs and Laments where he transcends the bounds of time, place, and identity by placing seemingly unrelated historical figures, symbols and archetypes together. The supposed logic, rationalities and divisions are irrelevant and when one looks at the monumental frieze across the bank of the Tiber River, one sees a shared and common humanity marching towards a hopefully better future. And with this Clingman poses the very underpinnings of Kentridge’s political oeuvre:

“Could art be revolutionary without conforming to the prescriptions of political formula”

Following these reflective writings, Clingman goes on to provide comprehensive scopes into the art featured at the Royal Academy exhibition. On the screen, canvas, stage or paper, Clingman helps us understand motifs that permeate through Kentridge’s work and by drawing on Kentridge’s line of thought, Clingman embraces the philosophical undertones that inform the artist’s use of shadows, subjects, space, and scale. We then see Kentridge as a fine artist, but as a romantic poet, a philosopher, a satirist, a historian and equally as a futurist. We see him as a re-imaginer of stories where all the Sybil’s of Greek and romantic literature are given the face of an African ballet dancer in Soweto. It was within these pages that I truly understood the virtuosity of William Kentridge. Here is a man who has seen worlds, individuals, people shrunk to their limitations and showed us through art that those limitations exist only if we let them.

By Lukanyo Mbanga