Who is David Goldblatt?

There are very few words appropriate or even necessary to describe David Goldblatt’s gift for the lens. The silence of his stills speaks of an atmosphere, character and soul that render spoken syllables useless. The South African photographer is known for capturing moments of Apartheid for all its depth and banalities. From his teen years, Goldblatt harnessed his skills, and at 33 years old he became a full-time photographer, chronicling the people and structures of the apartheid system.

A Documenter vs An Artist: Is there a need for distinction?

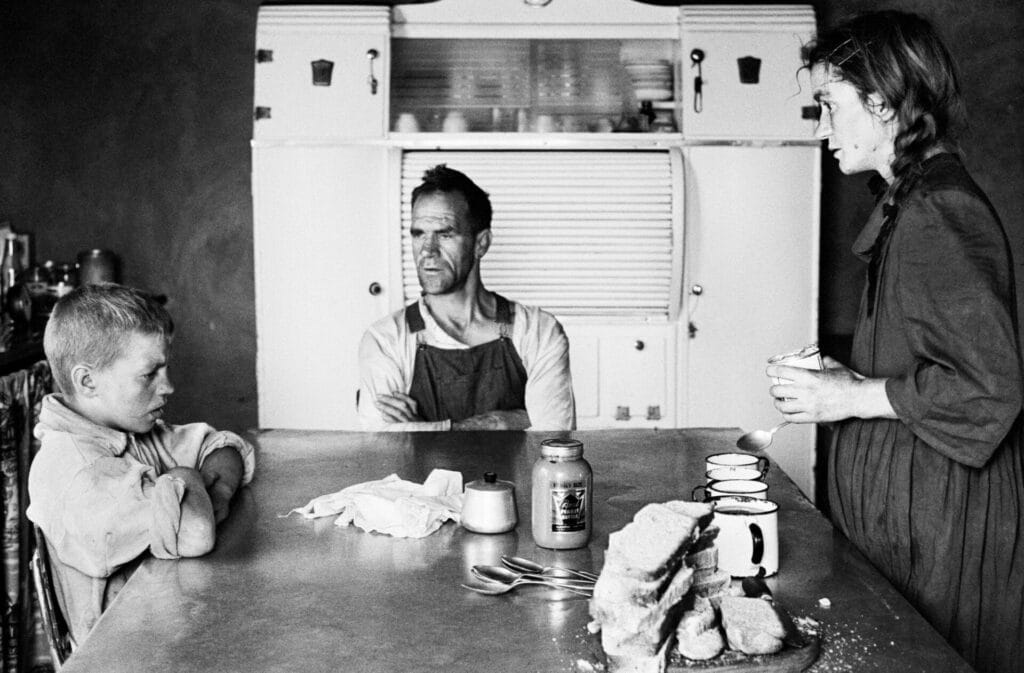

Believe it for not for a good part of his career, Goldblatt never thought of himself as an artist but rather a documenter. With this, he wanted to disassociate feelings and skewered perceptions. He wanted to capture moments for what they are and what they depict. Until the 1990s he only photographed in black and white, believing the absence of colour will serve a more objective view. How wrong he was in both regards. His approach to documentary is what reflects his unique artistry. Documentary can’t really be objective because it’s the documenter that gets to choose who and what is shown. The documenter guides the story and he or she can lead it anywhere.

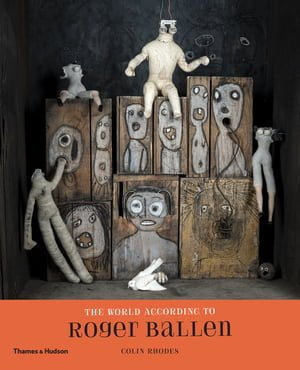

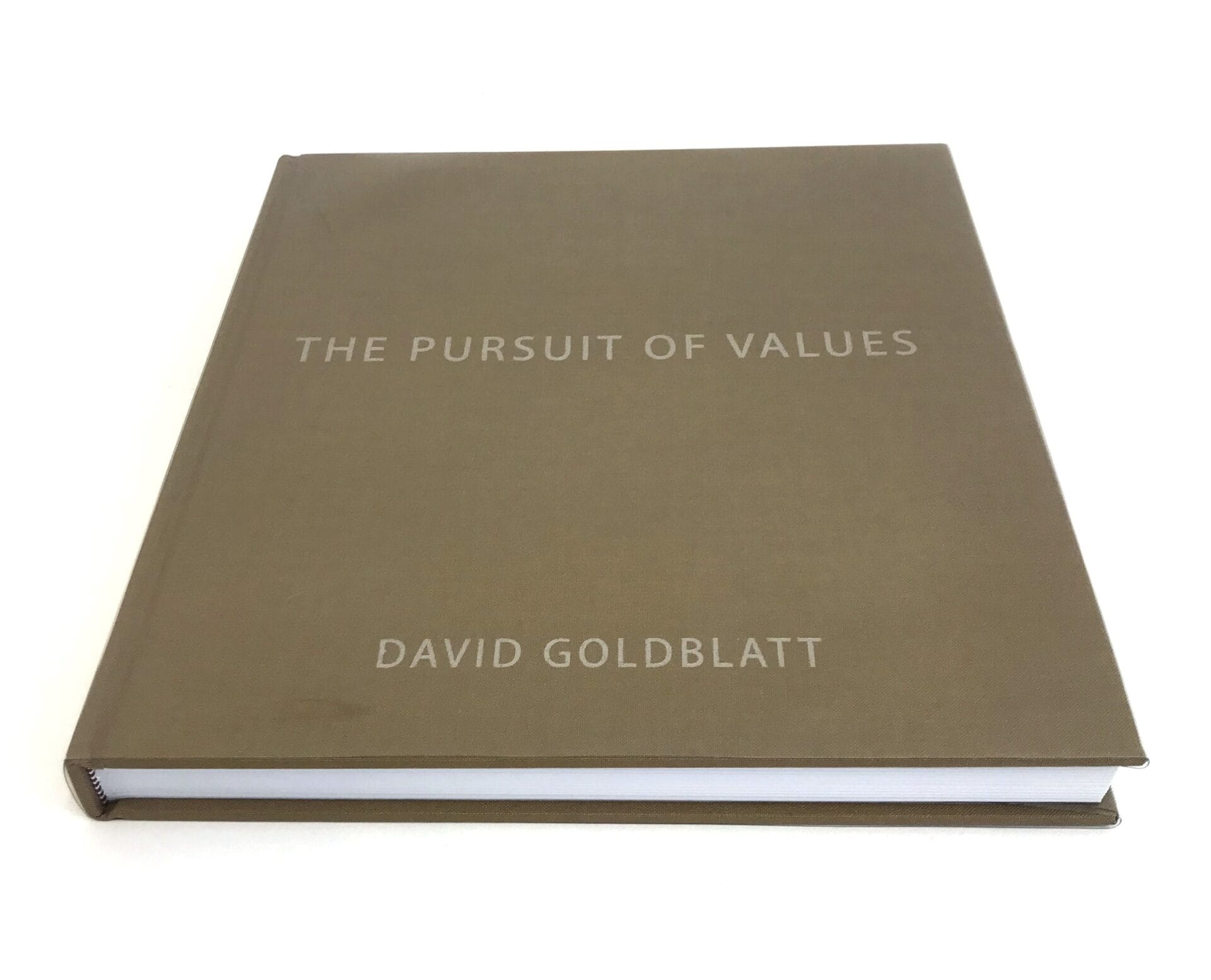

The Pursuit of Values depicts his modus operandi brilliantly. The book contains images from the early days spanning to his very last. Most are in black and white. Although this palette may remove more telling aspects of the scene, there is still something more pronounced and evocative about these black and white images. Slumped postures, thick folds of skin, foreheads wrinkled in frowns or teeth grinning and glistening stark against a darker backdrop of skin or shadow. Its mood is bewitching.

To Show and Not Tell the Complexity

When paging through this stunning catalogue, Goldblatt’s eye for paradox, dichotomy and human fragility are unmissable. It’s a wonder how he was often criticized for having no political voice or showcase of activism when the nature of his work offers something more stirring. Goldblatt doesn’t interrogate for us. He calls us to do that for ourselves. He prompts us with intentional, cheeky titles or captions to his images such as, “Sitting at the kitchen door, he said affectionately, to the child, ‘Ja, wat maak jy hier jou swart vuilgoed.’” Looking at the image once, you can’t help but laugh at the unexpectancy of the description. But reading the caption again and looking back at the old white man on his stoel with a black little boy peering uncomfortably from outside…and the subtext becomes quite unsettling.

In Goldblatt’s work there are hardly pointed victims or villains. Each of Goldblatt’s subjects are simply products of a society that placed them with the favorables or the unfavorables. One only becomes aware of what their own emotions and social literacy will make of the depictions. He tells it for what is and we are left to decide whether it should or shouldn’t be, or if we sympathize or not.

Ex-Offenders at the Scene of Crime is perfect example this. Reflecting on the crime that plagues South Africa, Goldblatt compiled a catalogue that captures criminals in their freedom or parole. The fact that they’re offenders completely allude you. You find yourself searching for the criminality in their eyes but really you feel a sympathy. The human is more potent than the monster. In fact, you feel the true monster hiding beyond the frame is society. The world of haves and have-nots and the fungi of desperation it fosters as a result.

Beauty in the Mundane

I think what makes Goldblatt’s images so captivating is how he romanticizes the ordinary. How he gives new meaning to routine and adds depth to the rural and rustic. Whether it’s a shop assistant leaning on a clothing rail, laundry hung on a single line running across the dry cape planes, or an old man sitting on a stoel while watering his garden. There’s always more to it. It stares right at you and says: ‘Well, what do you make of me?’

Written by Lukanyo Mbanga

More on South African Photography