Why Do We Collect?

Collecting is a complex and personal pursuit, which can be tied to an instinctual need to maintain a legacy. The books and knowledge we hold onto, whether we intend to or not, inform the next generations to come. Although many of us feel an almost sentimental connection to the items we collect, the motivation for collecting books varies. Some individuals collect purely to gain knowledge, aesthetical collectors find appreciation in the design and the binding process and others collect to acquire investments or titles which will increase in value over time. Fine art books are an amalgamation of these niche collecting habits. They are an invaluable source of knowledge with many art admirers aiming to create a reference library with information which is not as widely accessible as other subject matters such as botany, zoology or architecture. Fine art books are also an aesthetical collecting choice for many as these books create a merger between visual art and the art of bookbinding and design. There are many instances where these books are an artwork within themselves which not only appeases the aesthetical collector but also those who collect potential investment titles as these books can have the potential of increasing in price over the years.

William Kentridge has a prolific range of publications perpetuating this unification of aesthetical collecting, reference and investment titles. The Lexicon and Waiting for the Sibyl by William Kentridge are extensions of his body of works and examples of his playful need to experiment with different formats. Waiting for Sibyl reflects on the production of the opera, composed by Nhlanhla Mahlangu and Kyle Shepard, which was produced for the Opera House in Rome. The book itself was made during the COVID-19 pandemic and was a direct response to the restrictions and limitations put on opera house productions. It not only significantly emulates Kentridge’s motifs for the stage production, but it also speaks to a particular time in history when the arts were limited in their interactions with their audiences and new ways to connect to an onlooker where needed. The Lexicon by William Kentridge acts as a flip book which is filled with reproductions of Kentridge’s work – the flip-book function animates his work into a constant morphing image which changes from a cat to a coffee pot over the duration of the book. Titles such as these are an extension of the artist and in a way collecting limited edition books such as these is owning a part of the artist’s oeuvre.

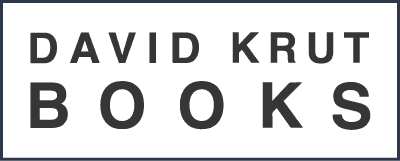

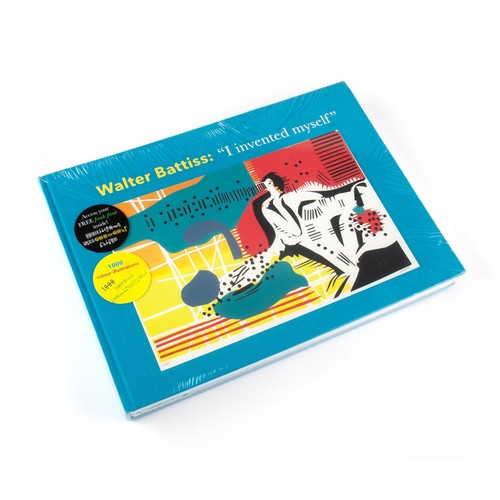

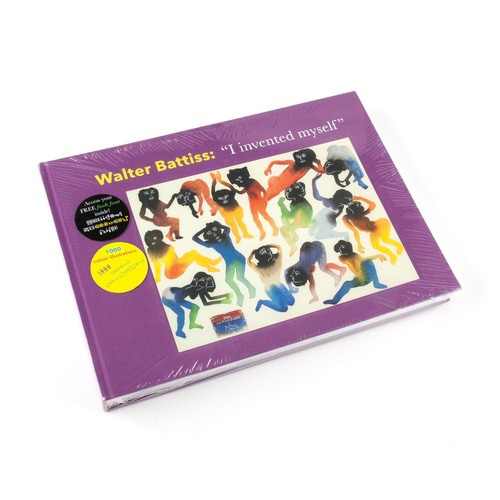

Furthermore, the lineage and canonical understanding of art is captured by these kinds of publications. Once an artist has passed there is no first-hand knowledge of that artist’s process which makes publications which capture the extensive body of work of any artist essential. For example, Walter Battiss’s “I Invented Myself” is one of the most extensive records of Battiss’ work and it has become an essential part of any Battiss admirer’s library. Publications which record artist bodies of work are essential to art historians and without these publications, information runs the risk of becoming distorted or simply fading away.

The reason we collect fine art books varies depending on the individual’s intended purpose for their library. Whether we want to extend our knowledge of the arts or wish to collect books that will increase in value over time – book collecting is a compulsion felt by many.